Maria / culturala

What’s fascinating about this film is how subtle, direct and relatable the woman Heba plays is. Where did the idea of this character appear?

Liz

I wrote this story before I ever picked up a camera, so this woman wasn’t written as a character, she was just written in my notebook and it was just for me. The character is me and it was especially me at the time I wrote it about 7 years ago. Once I started working with video it came back to my mind and in the same thought, I knew I wanted Heba to be the actress. I wasn’t sure if we’d be able to pull of the project, but I knew she would get it and I just wanted to share it with her. On set it was just her and I 90% of the time. I didn’t give her much direction; I would mainly just describe how the character would be feeling in the scene and then Heba would have to conjure that feeling and I’d capture it. Also, we were sleeping in the tent from the film and waking up to the Nile every morning like the character. When she’s in the boat I’m in there with her, when she looks scared going through rapids, she is scared, if the camera is a little shaky it’s because I was scared too. I think the character is relatable because she was never really fictional.

culturala

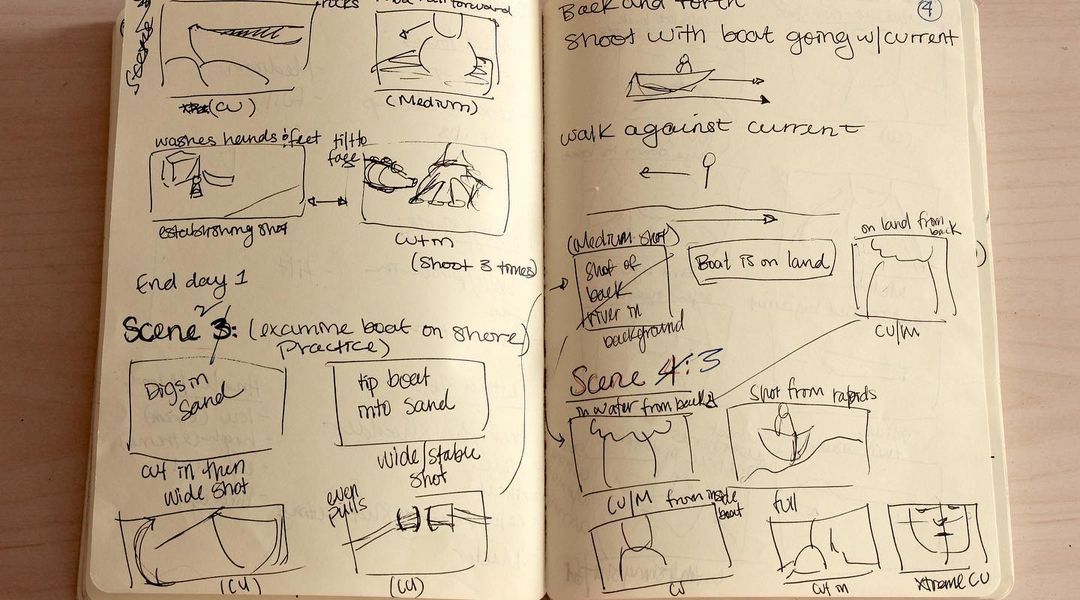

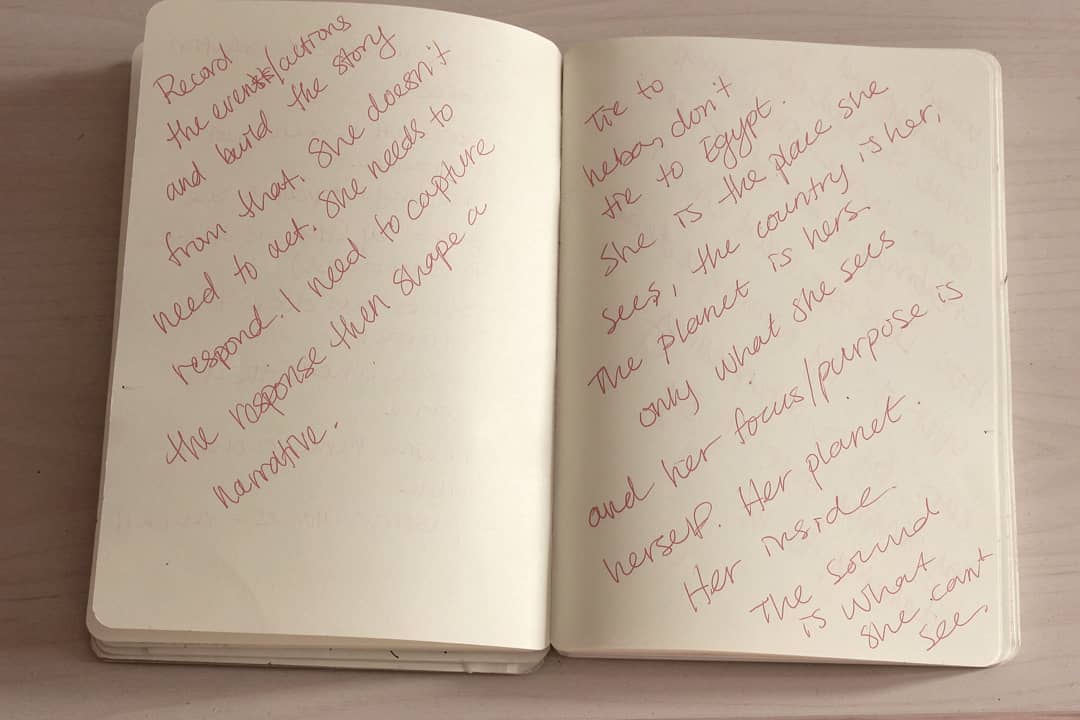

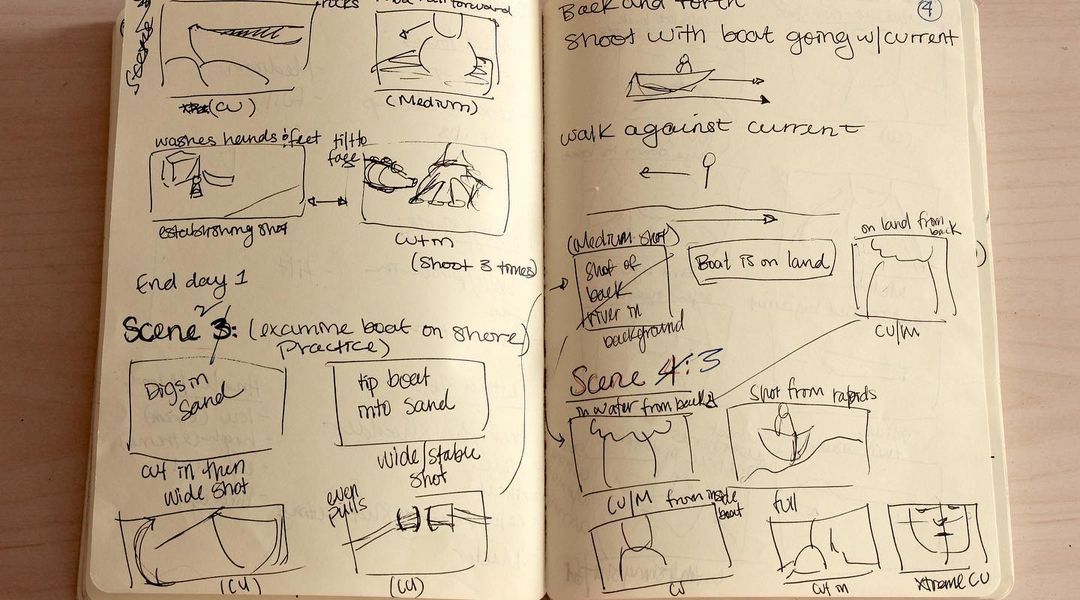

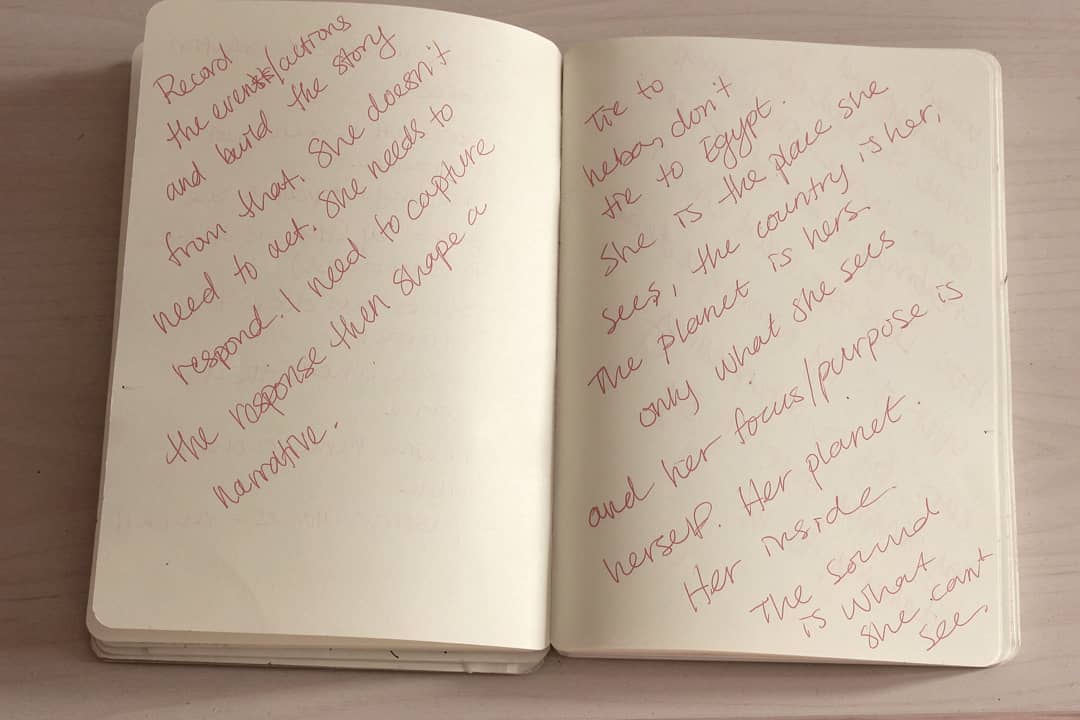

In the notebook, you can see even clearer the relationship between filmmaker and actress, between the two best friends, a setting that sets the tone for a film full of texture. It explains, or at least says out loud, this very familial setting of affection and unconditional understanding that the story holds.

culturala

When I first watched the film, I wasn’t in a very good place – so seeing her breakdown, seemingly over nothing and everything, in the water, was a great release. Especially with how beautifully it was filmed. What were your conversations around this “breakdown”?

Heba

We did the film at a very difficult time in my life. I’d just moved back to Cairo after spending a year and a half in London. I was ungrounded, confused and a bit lost. When we talked about the scene, everything just clicked! The peak in destroying the tent that was my house was, in my head, my struggle with moving: I move a lot, I don’t stay in one place more than two years, and I think coming back from London made me tired of it. I have also been struggling with the idea of home: what is it and where? I was at a place in my life when I was redefining what home means and destroying it in the film was what I needed at that time. While I was dancing, we played a song that I listened to a lot after my father passed away. He died when I was in London. So I was completely alone in dealing with my grief and then having to push it aside. In that moment I was grieving him, my nonstop moving, my ever-changing life. Grieving and accepting. It just felt like it was written for me years ago to just happen on this specific moment, by the Nile in Aswan. It was magical and exhausting. I am grateful to Liz for this scene and everything I felt during it.

Liz

Release is the right word. To me, she’s there on that island to build herself. To establish a physical and emotional resilience through her home, the water, the boat, and her body. She’s trying to master these things, bring them under her control and when she falls from the boat, the river completely masters her body and any resilience she had built cracks. I think sometimes in that state we turn and start destroying anything left standing. She’s reached her physical and emotional limit and has failed to master herself. The dancing was entirely in response to Heba, it’s not in the original story. Heba is a very reserved person but when she’s dancing, it’s pure joy and release. We wanted that to be the character’s reestablishment of herself.

This scene is the crux of the film, I think. We only filmed it once and it’s all from just one shot because I didn’t want to put Heba through it twice and I knew if I missed it the first time, it wouldn’t be honest in a second take. I asked her to conjure up a memory, and whichever one she did, she was angry and then she was sad and then she was exhausted and that’s what you see on screen. It was very, very difficult to stay behind the camera and not comfort my friend until I had gotten the shot. It was intense and uncomfortable. Afterward, we just sat there for a while and I think we were both completely spent.

culturala

What is the most magical thing you learned from making this film?

Heba

(Jumping in the Nile haha!) That I can be an actor. I always wanted to perform, and I remember I went to my father who was a theatre director and actor, and I asked him how I can start. I was 7. He then told me that I cannot: I have a low voice and I am too emotional. I forgot this dream for over 30 years. Being in the film and working with Liz who could see my interest and talent without me even mentioning my desire to her was very heartwarming and reassuring. My emotionality and sensitivity that has always been shamed was what made my performance the way it was, and I am so proud of it.

Liz

I think it taught me the kind of art that I want to make which was a big deal for me at the time and still is. I had been discouraged explicitly and implicitly, especially in art school, from making “sentimental” art and felt myself being pulled toward an idea that my work must have weight and universal significance. That it has to appeal more to cynicism or satire, which made me look at my work as immature and naïve, and caused quite creative crisis. When I brought the idea to Heba, I knew she would help me set that aside and recognise this story I had written as weighty and significant because of its emotion. What was magical about making this film was working with Heba. It would be a long answer to say all the reasons why but in brief, the making of the film was the making of myself as an artist, as a woman, as a friend. It was my first film; not every project I do will feel like that… But I’m so grateful for this film because it’ll always serve as a reminder that I am capable and allowed to make work that is truthful, sentimental, and challenges me as an artist technically and emotionally. That’s the kind of work that I appreciate and respect so why am I going to let anyone tell me it’s immature?

Maria / culturala

What’s fascinating about this film is how subtle, direct and relatable the woman Heba plays is. Where did the idea of this character appear?

Liz

I wrote this story before I ever picked up a camera, so this woman wasn’t written as a character, she was just written in my notebook and it was just for me. The character is me and it was especially me at the time I wrote it about 7 years ago. Once I started working with video it came back to my mind and in the same thought, I knew I wanted Heba to be the actress. I wasn’t sure if we’d be able to pull of the project, but I knew she would get it and I just wanted to share it with her. On set it was just her and I 90% of the time. I didn’t give her much direction; I would mainly just describe how the character would be feeling in the scene and then Heba would have to conjure that feeling and I’d capture it. Also, we were sleeping in the tent from the film and waking up to the Nile every morning like the character. When she’s in the boat I’m in there with her, when she looks scared going through rapids, she is scared, if the camera is a little shaky it’s because I was scared too. I think the character is relatable because she was never really fictional.

culturala

In the notebook, you can see even clearer the relationship between filmmaker and actress, between the two best friends, a setting that sets the tone for a film full of texture. It explains, or at least says out loud, this very familial setting of affection and unconditional understanding that the story holds.

culturala

When I first watched the film, I wasn’t in a very good place – so seeing her breakdown, seemingly over nothing and everything, in the water, was a great release. Especially with how beautifully it was filmed. What were your conversations around this “breakdown”?

Heba

We did the film at a very difficult time in my life. I’d just moved back to Cairo after spending a year and a half in London. I was ungrounded, confused and a bit lost. When we talked about the scene, everything just clicked! The peak in destroying the tent that was my house was, in my head, my struggle with moving: I move a lot, I don’t stay in one place more than two years, and I think coming back from London made me tired of it. I have also been struggling with the idea of home: what is it and where? I was at a place in my life when I was redefining what home means and destroying it in the film was what I needed at that time. While I was dancing, we played a song that I listened to a lot after my father passed away. He died when I was in London. So I was completely alone in dealing with my grief and then having to push it aside. In that moment I was grieving him, my nonstop moving, my ever-changing life. Grieving and accepting. It just felt like it was written for me years ago to just happen on this specific moment, by the Nile in Aswan. It was magical and exhausting. I am grateful to Liz for this scene and everything I felt during it.

Liz

Release is the right word. To me, she’s there on that island to build herself. To establish a physical and emotional resilience through her home, the water, the boat, and her body. She’s trying to master these things, bring them under her control and when she falls from the boat, the river completely masters her body and any resilience she had built cracks. I think sometimes in that state we turn and start destroying anything left standing. She’s reached her physical and emotional limit and has failed to master herself. The dancing was entirely in response to Heba, it’s not in the original story. Heba is a very reserved person but when she’s dancing, it’s pure joy and release. We wanted that to be the character’s reestablishment of herself.

This scene is the crux of the film, I think. We only filmed it once and it’s all from just one shot because I didn’t want to put Heba through it twice and I knew if I missed it the first time, it wouldn’t be honest in a second take. I asked her to conjure up a memory, and whichever one she did, she was angry and then she was sad and then she was exhausted and that’s what you see on screen. It was very, very difficult to stay behind the camera and not comfort my friend until I had gotten the shot. It was intense and uncomfortable. Afterward, we just sat there for a while and I think we were both completely spent.

culturala

What is the most magical thing you learned from making this film?

Heba

(Jumping in the Nile haha!) That I can be an actor. I always wanted to perform, and I remember I went to my father who was a theatre director and actor, and I asked him how I can start. I was 7. He then told me that I cannot: I have a low voice and I am too emotional. I forgot this dream for over 30 years. Being in the film and working with Liz who could see my interest and talent without me even mentioning my desire to her was very heartwarming and reassuring. My emotionality and sensitivity that has always been shamed was what made my performance the way it was, and I am so proud of it.

Liz

I think it taught me the kind of art that I want to make which was a big deal for me at the time and still is. I had been discouraged explicitly and implicitly, especially in art school, from making “sentimental” art and felt myself being pulled toward an idea that my work must have weight and universal significance. That it has to appeal more to cynicism or satire, which made me look at my work as immature and naïve, and caused quite creative crisis. When I brought the idea to Heba, I knew she would help me set that aside and recognise this story I had written as weighty and significant because of its emotion. What was magical about making this film was working with Heba. It would be a long answer to say all the reasons why but in brief, the making of the film was the making of myself as an artist, as a woman, as a friend. It was my first film; not every project I do will feel like that… But I’m so grateful for this film because it’ll always serve as a reminder that I am capable and allowed to make work that is truthful, sentimental, and challenges me as an artist technically and emotionally. That’s the kind of work that I appreciate and respect so why am I going to let anyone tell me it’s immature?

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.