A playful, punk rejection of cinematic tropes, shot through with irony, 16mm grain, and ghostly speculation—

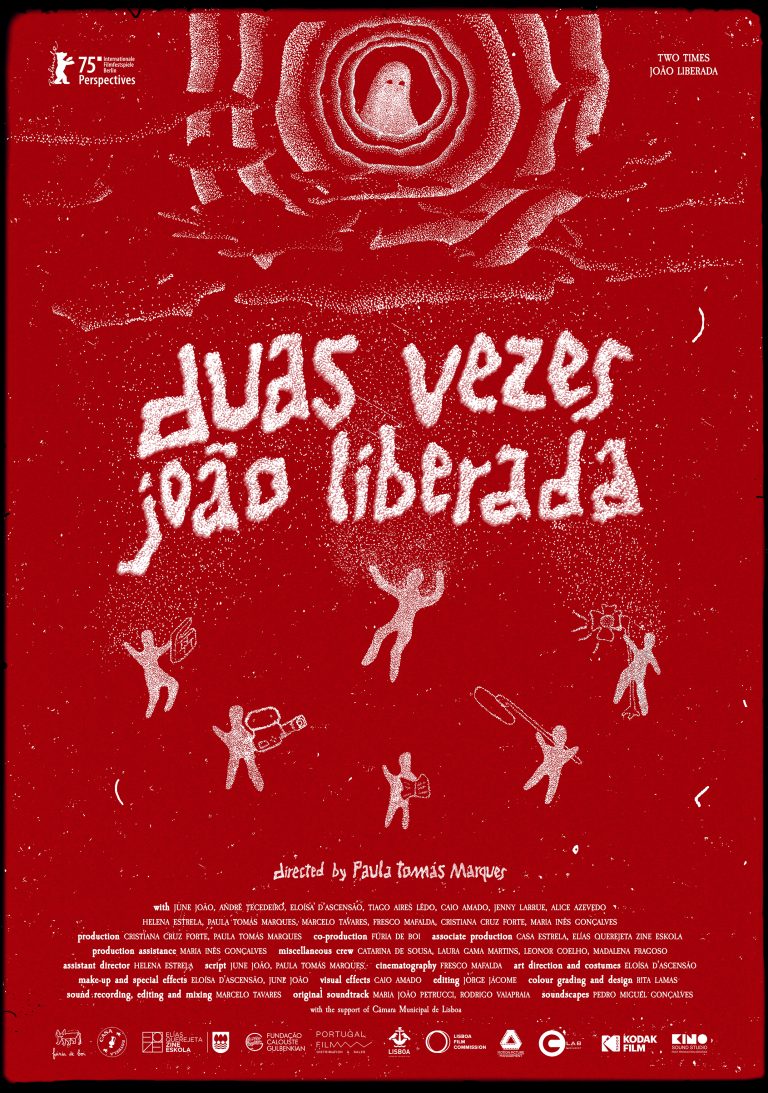

What starts as a self-serious historical biopic quickly reveals itself as something much weirder and more alive: a metanarrative about authorship, queer identity, and the politics of representing history. In Duas vezes João Liberada, director Paula Tomás Marques uses ghostly visitations and film-within-a-film chaos to challenge patriarchal storytelling and reclaim the past through irreverence and imagination.

Nothing triggers my cinematic allergies quite like oversentimentality. The opening scenes of Duas vezes João Liberada, the feature (1) debut from Paula Tomás Marques which premiered at the 2025 Berlinale, seem to set the stage for yet another stiff, self-important period biopic (2). But soon enough, the illusion shatters—we are not in some bygone era, we are on a chaotic modern-day film set. The story follows João (played by June João), an actress cast as the gender-nonconforming João Liberada, a historical figure persecuted by the Inquisition in 18th-century Portugal. Initially excited to portray a main character, João quickly clashes with the director, Diogo, who insists on portraying Liberada as a tragic martyr—a move all too common in historical films—rather than a fully realized person with agency, own thoughts, feelings, and contradictions.

As the story progresses, the ghost of Liberada begins to haunt João’s dreams—but not as some ethereal, tortured soul. Instead, they speak in a sarcastic, contemporary voice, gleefully mocking Diogo’s approach to making this film. “Schubert? Really?” (3) they scoff, ridiculing the clichéd musical choices meant to squeeze out emotion from the audience while the character encounters hardship. The irony is sharp: while Diogo’s vision flattens the past into a predictable tale of suffering, the film itself pushes back, reviving Liberada as a witty, modern commentator. This tension between a solemn, conventional portrayal of history and a cheeky, irreverent reimagining drives the film’s subversive energy. When Diogo suffers a mysterious paralysis and can no longer finish the film, João is left navigating the production while facing the unanswerable questions—not just about the fate of the project, but about her own connection to Liberada’s spirit and story.

A metanarrative, a punk (4) critique of historical storytelling, and an exploration of gender identity and queer representation in cinema

Duas vezes João Liberada operates on multiple levels—João as the historical figure, João as the actress, João as the ghost—layering history, filmmaking, and the supernatural into a single, destabilizing conversation. Shot on 16mm in Lisbon, its tactile, analog aesthetic embraces glitchiness—grain, lighting shifts, color distortions add to the playful nature of this piece. The film’s director Paula Tomás Marques refuses to conform to the rigid structures of a biopic or the conventional rules of filmmaking itself.

How do we represent the past, particularly when it comes to trans and gender-nonconforming figures whose histories have been erased, distorted, or appropriated?

Duas vezes João Liberada operates on multiple levels—João as the historical figure, João as the actress, João as the ghost—layering history, filmmaking, and the supernatural into a single, destabilizing conversation. Shot on 16mm in Lisbon, its tactile, analog aesthetic embraces glitchiness—grain, lighting shifts, color distortions add to the playful nature of this piece. The film’s director Paula Tomás Marques refuses to conform to the rigid structures of a biopic or the conventional rules of filmmaking itself. Where most historical dramas aim for gravity and reverence, Marques leans into irony. In this way, the film aligns with a longstanding tradition of using humour to expose and critique rigid norms of patriarchal storytelling. These norms are personified in the character of Diogo, the male director whose vision for the film is authoritative and tragic. His mysterious paralysis reads almost symbolic: the collapse of patriarchal control over the narrative.

Beyond its visual and narrative inventiveness, the film-within-a-film framework opens up deeper ethical questions: How do we represent the past, particularly when it comes to trans and gender-nonconforming figures whose histories have been erased, distorted, or appropriated? The team echoed this difficulty in the post-screening Q&A, where they noted how rarely the historical record preserves the lives of gender dissidents, making even the act of searching for them a speculative exercise. With the dilemmas around the ethical stakes of representation, authorship, and the projection of identity onto character, they offer something vibrant, messy, and alive—a reclamation of agency in the present. Not a historical reconstruction, but rather a radical act of imagining.

Intelligent, wildly original, and with the potential to become a cult classic, Duas vezes João Liberada asks urgent questions about how history is written and who controls its narratives. And crucially, it does so without pretense, never taking itself too seriously. Like Liberada’s ghost, the film is too smart—and too fed up—to fall for clichés.

footnotes:

(1) feature film: a film that has a runtime of over 60min. This distinction is primarily used to separate films into the category of a short film (below 60min) or a feature film (over 60min), no matter what genre.

(2) biopic: biographical film; a film that dramatizes the life of an actual person or group of people. Such films show the life of a historical person and the central character’s real name is used

(3) Franz Schubert: Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras

(4) punk: I used this term to underline the defiance of convention, in this case historical storytelling in film

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.