“Psychosis isn’t just personal—it’s societal too. Society judges whether you’re ‘mad’ or ‘normal’ according to its standards.”

In this conversation, Jen Debauche sheds light on the creative process behind the creation of her latest feature L’Ancre (The Anchor), her research of psychosis and all the elements that shaped it, reflecting on the significance of reclaiming the narrative around mental illness beyond its stigmas, and her special collaboration with the great Charlotte Rampling.

The Anchor (L’Ancre), directed by Jen Debauche, was one of the standout films at the 22nd edition of Doclisboa, held in October 2024 in Lisbon. The film, part of the International Competition, had its world premiere at the festival, where it was honored with both the CUPRA International Competition Jury Award and the TVCine Channels New Talent Award.

Jen Debauche lives and works in Brussels, where her work spans film and radio directing, research, and teaching. As a founding member of LABO BxL, a shared film workshop focused on photochemical practices, Debauche continues to work with the analog medium in an increasingly digital world. Her films—often hybrid works that blur the borders between fiction, documentary, and experimental cinema—have been showcased at prestigious international venues such as IFF Rotterdam, FID Marseille, and the New York Film Festival, among others.

The Anchor is Debauche’s second feature after L’oeil du cyclope (The Eye Of The Cyclops), and the culmination of several years of research on the concept of madness and its socio-cultural construction and interpretations. The film intertwines personal testimonies, desolate Arctic landscapes, and experimental techniques to offer a sensitive and poetic meditation on psychosis—an approach explored in depth in my review here.

Maja: Your film seems to bridge the artistic and the personal, and in your research, you’ve explored fascinating intersections—like those between analog film processing and clinical psychiatry. What inspired you to begin this project?

Jen: When I make a film, there are always multiple starting points. First, there’s desire—the desire to meet a certain person, to capture a particular face or landscape, to explore a specific subject, to collaborate. And then there’s necessity—a need to respond to something deeply personal. I often feel like I’m making a film for someone.

This film was, at its core, born out of friendship. A close friend of mine, whom I met in film school 25 years ago, experienced a psychotic episode in 2016. I wanted to understand what was happening to her and after a forced psychiatric hospitalization, I welcomed her into my home. At the time, I was also in a state of palpable fragility, and this cohabitation was an intense experience. There was fear, of course—seeing a person you know so well suddenly become someone else. Yet despite that fear, and despite my efforts to embrace this new version of her, my friend’s delirium carried something universal. I found myself wondering about the transformative, even creative potential of psychosis.

At the same time, I was immersed in discussions on psychiatry. Many of my friends work in the field, particularly at La Borde, a well-known psychiatric clinic in France recognized for its unique approach to institutional psychotherapy. Founded in the 1950s by Jean Oury, it seeks to heal not just patients but the institution itself. Their philosophy—rethinking power structures and giving voice to those with lived experience—deeply influenced me.

Parallel to this, I received funding for a three-year research project on madness, society, and cinema. This allowed me to meet artists, filmmakers, psychotherapists, and philosophers, forming a discussion group that became crucial to shaping the research in its early stages. We explored films on mental illness—documentary and experimental works—while engaging with key thinkers who have influenced the understanding of psychiatry and alternative approaches to mental health, such as Félix Guattari, François Tosquelles, Fernand Deligny, and Marie Depussé. This research led to two radio documentaries I produced on the theme of psychosis.

I wanted the film to center the voices of those who had lived through psychosis, treating their experience as expertise. I also drew from mental health professionals who described psychosis as a storm one must navigate—an idea that reinforced the boat metaphor in my film. After the storm, one must be able to recount the journey, to integrate it into something larger. That idea of storytelling—of reclaiming one’s narrative—became a core theme of The Anchor.

Maja : How did you approach your research process? Psychosis must be such a personal and vulnerable experience to go through for an individual.

Jen: Psychosis isn’t just personal—it’s societal too. Society judges whether you’re “mad” or “normal” according to its standards. This raised many questions: How do psychoses emerge? How do we recover after trauma? What tools are available for recovery? What does psychosis reveal about us and the world? I wanted a collective approach to these questions, which is why the research phase was so important. When the idea for a radio documentary emerged, people naturally came forward to share their stories, which was incredibly stimulating.

The process began with sound and audio interviews. This made the production lighter and less intrusive, as participants felt more relaxed to share without the presence of a camera. It was crucial to respect the people who shared their stories so I made sure to get everyone’s approval before releasing the radio documentaries and the film. Editing was done with care, alongside my trusted collaborator Sébastien Demeffe.

It was quite challenging to respect anonymity while staying true to my filmmaking vision but with co-writer Julie Labas, we carefully explored how to structure the narrative and fictionalize elements while staying close to their original words.

Maja: Sound in your film really adds to the layers of the emotional journey. Could you talk about your choices in this regard?

The soundtrack is the backbone of the film. In The Anchor, the characters remain anonymous; their words give them existence, with the exception of one character played on screen by Charlotte Rampling. The Arctic Circle landscapes are there to accompany the voices, much like an immersive soundscape.

My approach, grounded in my self-taught work with 16mm film—hand-processing, editing, and exploring its materiality—involved creating the soundtrack separately and turning it into a space for experimentation. Working off-sync, without direct sound, created a playful freedom. I love turning constraints into a playground!

In terms of music, my dream became reality: meeting Fred Frith, the incredible British composer. I had admired his work for decades, so it was a privilege that he agreed to join the project despite its limited budget. We collaborated remotely, and then he made a stop in Brussels during his European tour, armed with his guitar to create mesmerizing sounds for the film.

Another signature in the soundtrack came from the Arctic Circle residency, an annual expeditionary program that brings together artists, scientists, and educators to explore the high-Arctic Svalbard Archipelago aboard a research ship. Surrounded by ice, I met many luminous souls, including P. Alexander Bergeron, an extraordinary singer. His sublime voice had accompanied our journey, leaving a special mark. After the residency, he generously contributed his crystalline voice to the film, fragile yet powerful. It felt completely natural to include this imprint in the film.

Maja: It seems there are many layers of inspiration behind your film. What led you to shoot in the Arctic Circle?

Jen: Indeed. It was a long journey with many detours: theoretical research, building a film and bibliography, meetings, collaborations, and technical exploration. The film was shot in 16mm black and white, and I reworked part of it in the lab at LABO BxL, where I’ve been exploring photochemical processes for about twenty years. Some segments were crafted with filmmaker Gaëlle Rouard, through a meticulous process, sometimes frame by frame.

I immediately envisioned a boat as a metaphor for this journey and ice as a metaphor for the psyche. Metaphor expands meaning and creates larger spaces that can be filled with the unexpected or imaginary. It accelerates the creative process, connecting images, sounds, and gestures. I never intended to illustrate the testimonies but rather to accompany them—metaphor over illustration. Evoking rather than showing.

I got accepted to The Arctic Circle residency which made the boat journey possible. Bringing together about thirty artists, it gave the production a boost. I shot most of The Anchor’s crossing sequences aboard the L’Antigua boat.

I knew that Arctic landscapes would be essential in transitioning from the ‘radio’ to the ‘cinema’ stage. These landscapes provided the space for anonymous voices to unfold, filmed as characters rather than mere backdrops, conveying emotion at its deepest.

Maja: The landscapes and nature shots in your film made me think of climate change and the disruption in the natural world. Was this something you had in mind from the get go?

Jen: Yes, exactly! Going to the North Pole was almost a metaphor in itself. For me, it’s the place where you can materialize all the “madness” of the world. When I see images of collapsing icebergs, I think of how humanity is accelerating the planet’s destruction.

In The Anchor, cracks and breakages represent both psychic disruption and the destruction of the world by humans. I played with these resonances, blending inner and outer disturbances to make a personal story feel universal.

Maja: In Psychosis is a Mental Crisis, Not a Disease, psychotherapist and scholar Stijn van Gelles argues that psychosis is a disruption of one’s personal narrative, rather than merely a disease. He critiques the framing of psychosis within the biomedical model, which leads to treatment focusing only on institutionalized and medical care. Instead, he advocates for treating the mind, not just the brain. One quote that struck me was, “A therapist doesn’t need to be afraid of the strange and bizarre, of the things that exist only inside someone else’s head. Being afraid makes it harder to connect with others. If you want to work together to find new anchor points, you need to move beyond your fear.” He mentioned ‘the anchor’! It made me wonder if there’s a connection for you, or if this was purely coincidental. What does ‘the anchor’ mean to you?

Jen: Ah, yes! The title The Anchor came to me immediately and stayed until the end. It’s a metaphor that opens up possibilities. Anchoring oneself in life is never simple: you have to face your fears, stay afloat, keep your head above water, and avoid drifting. You must stay on course, but also accept the uncertainty of the journey.

In navigation, dropping the anchor during a storm risks the boat breaking apart or spinning in circles. You have to weather the storm, confront the elements, and only when the calm returns can you finally moor. The anchor both holds us back and allows us to reach solid ground. That’s where the title comes from.

I think Van Gelles is right but I am not a psychotherapist. “Psychosis as a disruption of personal narrative”—that’s so well said! It really resonates with the importance of rebuilding one’s story. But overcoming the fear of psychosis isn’t easy. Someone in crisis can be terrifying, and we’re often not equipped to handle it.

Still, with real listening, you can access so much. When I listened to my friend’s delusions and let go of my own rationality for a moment, I could grasp certain concepts. She was analyzing the world, defining humanity’s flaws, and singing about her deep connection to the universe. Her words were undoubtedly delusional, but they traced lines, composed melodies, and expressed a world with its own logic, its own codes, and its own laws.

Maja: In Movies and Mental Illness Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, and Ryan M. Niemiec, discuss portrayals of mental illness in film, starting from the inception of the medium. For many people, films and television are the first source of knowledge about psychological disorders. Sadly, many of those portrayals are associated with violence, reinforcing stereotypes and leading to stigmatization. I found it beautiful that your film gives psychosis a new face with so much sensitivity and hope.

Jen: Thank you, that really touches me. It’s true—psychosis in cinema is mostly portrayed in thrillers or horrors, often through violence and stereotypes. And television? Even worse.

With The Anchor, it was important to show that psychosis can happen to anyone. It’s not rare. All over the world, people lose their grip. But in our society, experiencing psychiatric treatment often means being labeled—like a jar of jam, as my friend used to say. And that label sticks. Everywhere. Finding a job becomes a struggle, and even those around you, out of prejudice or helplessness, begin to view you differently. For me, cinema was the perfect space to give a voice to these experiences.

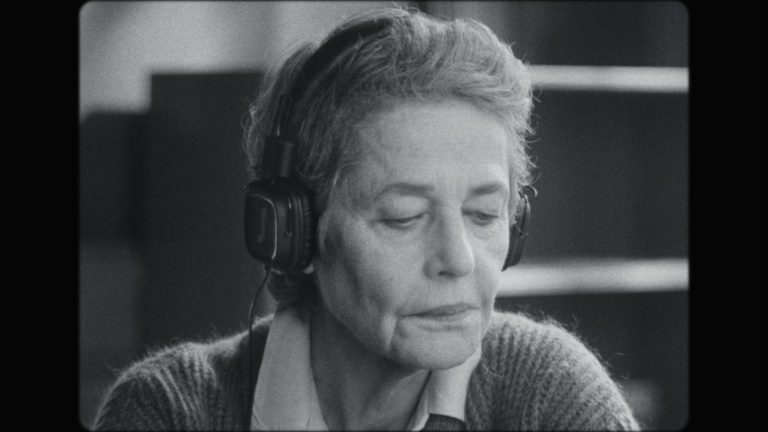

I wanted to highlight the expertise of those who have experienced psychosis. The idea that it is not just a symptom but also a form of knowledge inspired me. This is what I wanted to embody through the character played by Charlotte Rampling, shaped by the testimony of Florence, an incredible woman I interviewed for a radio documentary. Her story, slightly fictionalized, lies at the heart of the film.

Maja: Speaking of, how did you get the great Charlotte Rampling to work with you? What was the experience like?

Jen: Charlotte Rampling is in my film because I was stubborn. When the character came about in the writing, my co-writer Julie and I immediately envisioned her for the role. My production company reached out to her agents with the project proposal, and after a year of waiting for a response, there was still no news. The team tried to convince me to find someone else, but I said, ‘If she doesn’t say no, there’s still a chance it could be a yes.’

Eventually, she agreed to meet me. I took the train to Paris, and we had a fascinating conversation that lasted over three hours. We shared similar views on many topics, and most importantly, we really connected on a human level. In the end, she said yes.

Every moment working with her was a gift. Charlotte is a powerhouse—exceedingly professional, with quiet strength, razor-sharp precision, and incredible depth. What an actress! She’s truly extraordinary, and I absolutely adore her.

Maja: I love this motto—if it’s not a no, it might be a yes!

Jen: I work a lot with my impossible ideas. I ask myself, what’s my ideal impossible goal, and why not try to get there? Maybe it’s ambitious, but why not? You create with what you have, then you piece things together with whatever strings you can find!

Maja: Inspiring! Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me and share your thoughts! Congratulations on your beautiful film, and best of luck for the future.

Jen Debauche lives and works in Brussels. She is a film/radio director, researcher, teacher and founding member of LABO BxL, a shared film workshop focusing on photochemical practices.

website: https://www.jendebauche.com/

LABO Bxl: https://www.labobxl.be/

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.