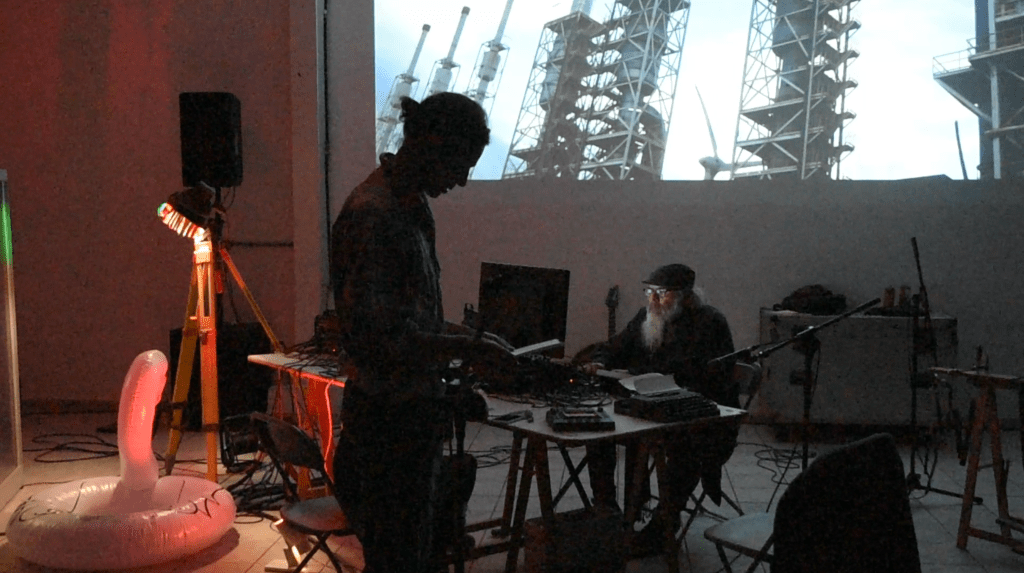

music: ‘El Regreso’ by Las Conejeras

(Guaya Milán, Onofre Montenegro and Patrick Germanier)

‘Es Para Mi’ by Salvador Hernández López “Borito”

Bruno Atkinson’s short film Profit Motive and the Endless Sea (2023) was filmed in the Canary Islands during the past year. Against a backdrop of almost-still footage, two parallel stories are told: that of the construction of the first desalination plant in Lanzarote solving the problem of water, and that of Shakespeare’s The Tempest through excerpts of Prospero’s solemn monologues. Beginning with the problem of there being no water on the island, the film uses the literature of engineers who built the desalination plant to tell the story of how they “overcame the ancestral limitations of a semi-desertic island territory like Lanzarote,” bringing water to the taps of the people. But, it seems, this changed everything not only to the better. It finishes on a solemn line from The Tempest, ‘Dost thou forget from what a torment I did free thee?’ in a meditation about hope beyond capitalism.

Bruno speaks of the story in the following words: ‘In both stories, we are told of the arrival of a settler who exerts power over an island because of his control over nature. Manuel Díaz Rijo, who comes from Madrid, arrives on the island of Lanzarote with a magical power learned from books. With it, he can transform seawater into drinking water, and therefore dictate the future of the island. Prospero, who comes from Naples, also arrives on an island with a magical power learned from books. With it, he can control nature, and so keep the population of the island under his control. He opens the trees, stirs the sea, extinguishes the sun, decides who will drink fresh water and who will drink brine. They both begin small; Rijo on an island devastated by aridity and stunted growth, Prospero on a rotten ship without a sail or friend. They are both motivated by an external force; Rijo by “progress”, Prospero by his daughter. And they both end up great; Rijo by proclaiming his power to a council of admirers, Prospero by exerting, exalting and then ultimately giving up his power over the island.

‘The film tries to point to Prospero’s obviously manipulative and violent tactics and rhetoric in Shakespeare’s play to expose Rijo’s narrative as also manipulative and deceptive, what Walter Benjamin rejects in his Theses on the Concept of History: a “linear, homogenous, quantitative conservative historicism, anchored in the ‘ideology of progress’”. Or, as Helen Scott writes, “history, documented by the victors”. In reality, Rijo’s desalination plant opened Lanzarote’s doors to the mass tourist industry, an industry almost totally reliant on the desalination of water from the sea, and as a result a vast, potent and poetically important architecture and culture of water was lost. Magnificent architectures based on indigenous methods of water collection and storage lie scattered around the island in a state of dilapidation and disrepair. A whole culture, architecture and psychology of water conservation and preservation is lost to dreams of never-ending resources created by those with a fundamental motive of profit.’

The story of the desalination plant, we are told, started in 1960. Water on the island came only from rainfall, so islanders had to rely on primitive means of water collection and storage. Cisterns and structures were, as the narrator in the film tells us, ‘cared for better than the children’. Donkeys carried barrels of water across dirt roads. Boats brought water from the mainland. Population growth remained stagnant and the quality of life was low, the rate of economic growth nil, and hope of anything changing not present in any form. Speaking to the Spanish Mayor of the Canary Islands, engineer Manuel Díaz Rijo comes up with the idea of creating a desalination plant to convert seawater into fresh drinking water. It’s not a new idea, but a technological solution not yet available on the island. Overcoming many odds, Rijo and a group of engineers manage to build the desalination plant which unlocks the potential of the island and causes ‘an upsurge of life.’ From then on, the potential of the island was unlocked and the sea became the great reservoir of Lanzarote. The dream of growth and progress had become a reality.

Maria / culturala

Profit Motive and the Endless Sea tells the founding story of capitalist control over the Canary Islands. How did you first encounter this history? And what made you make movies on the islands?

Bruno

I first came up with the idea after Emily Reed, a close friend and feminist researcher, was telling me of the hydro-feminist potential of The Tempest. I then moved to Lanzarote for work, where I was inspired by a group of artists who live and work with the history and culture of water on the island. But the main propeller behind making the film was when I discovered the documents, speeches and books that the engineers of the desalination plants have written since its installation in 1965. The way they spoke struck me as so similar to Shakespeare’s patriarch, there were so many parallels. So I chose to make a film that would use Shakespeare’s text, with its heavily subversive potential, to sort of denounce or pick holes in the narrative that the desalinators had created.

culturala

You speak about the narrative of capitalist expansion that incorporates the past only to justify its own presence in the future. All of that is currently on its head with the current climate crisis. What are your thoughts on the capitalist narrative of expansion? And what would you like people to do in response to seeing your film – do you have any particular ideas in regards to this?

Bruno

I’m not claiming that the material reality in Lanzarote is the worst situation in the world. If we are talking about the negative impacts of corporate expansion, there are examples which are far more pressing, where land is being devastated and communities destroyed on unimaginable scales. I am focusing more on the effect that fiction can have on reality. People with a motive (be it profit or otherwise) often distort the past in order to justify their actions into the future. For the desalinators, the fiction was: ‘There was nothing here before us; after us everything grew.’ Because of this narrative, a whole culture of collecting, storing and caring for water has been almost completely eradicated by what is ultimately a dream of infinite resources. Endless water, so endless growth, so endless profit. And I think this is pretty dangerous, because no resource is endless, and the availability of drinking water is one of the biggest problems we are currently facing on this earth. So I guess I’d like people to think more about who is telling the story of progress. And I’d love it if it made people think more about water, even if it’s just wondering how it gets to their tap.

culturala

What do you think changed by the creation of the desalination plant? The film speaks of traditions being lost, but you also write about some people on the island still working with the traditional ways of collecting water against what you call ‘the regime of desalination.’ Could you expand more on that?

Bruno

I think this is an interesting and quite difficult question. On the one hand, you could see the arrival of the Spanish desalination industry onto Lanzarote as a godsend for the islanders; opening up the island to the outside world, expanding the population and increasing the standard of living on the island. On the other, you could see it as having some pretty serious consequences, as the origin of an industry massively reliant on fossil fuels, plastic, water (imported in bottles) and vast swathes of illegal hotels and settlements built on protected land, while thousands of ancient structures are abandoned to the march of time.

However, as you mention there are still people who are working with and preserving the old culture of water on the island. I would point to the many islanders who still have working cisterns and who are partially or wholly reliant on rainfall for their intake of water, Nona Perera, who alongside the Canarian Government’s General Directorate of Cultural Heritage is restoring cisterns of particular scientific and historical value, Patrick Germanier and Simone Rüssli, who work closely with structures of water in their artistic practice on the island, and the countless historians, scientists, sociologists and environmental activists who are working to keep the history of water in Lanzarote relevant and alive.

culturala

The film is very beautiful, created as a collage of short clips where the camera is held very still. What made you use that technique? What do you think it brings?

Bruno

Thanks! In general I like the idea of still-frame films because they are, as Peter Hutton writes, ‘about taking the time to just sit down and look at things.’ It is also very simple to do when you have limited means. I was specifically inspired by John Gianvito’s Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind, another historical landscape film which, in his words, explores the ‘insidious and corrosive impact that Capital has upon the pursuit of a more egalitarian and just society, a quiet film about a violent past’. In my film, I wanted this stillness to be most prominent in the final section, where I visually document a small fraction of the huge number of water cisterns that exist on the island in a state of disrepair. This is less about quiet reflection on a past violent struggle (as in Gianvito’s film), and more about using silence and stillness as a sort of mute outrage or silent denunciation. There is a line of Caliban’s I could have put in: ‘I loved thee, and show’d thee all the qualities o’ the isle, the fresh springs, brine-pits, barren place and fertile: cursed be I that did so!’ but I thought it better for the film to speak this silently.

culturala

I’m also very fond of the way you play with silence, voice and music throughout the film which comes and goes in waves, creating this uncanny feeling of constant change. Where does the music come from? Do you usually work with audio in this way?

Bruno

The main track comes from a recording of a performance called ‘El Regreso’ performed by Guaya Milán, Onofre Montenegro and Patrick Germanier at the 9° Bienal of Lanzarote (2017/18). I think you’re right, it’s definitely a piece that’s concerned with change; as a project it aimed to reflect on the ‘island’s process of transformation, with the installation of powerful technology to accommodate the growing number of temporary visitors’. I like it because I feel it contains both the pulsating excitement of the promise of a shiny new start, but also the contradicting undercurrents of warning beneath:

'All this is taking place at the bottom of the energetic power plant, eternally running, releasing its toxic smoke day and night, to feed artificial lights and freezers, to satisfy the huge demand in drinking water, extracted and filtered in its entirety by the sea'

– Patrick Germanier

And the second song is by a canarian timple player who I first met in a tele-club (a small community restaurant), where he was singing about a series of natural springs that Canarian farmers used to take their goats over 70 years ago: three small puddles the size of a plate which would give water to 22 goats and 32 lambs. The lyrics of this song in particular translate roughly as: ‘it is a despair to me to see my countryman plough / it is a waste for me to see my countryman cry / looking at the sky to see if his hat gets wet / and go out / to his dreams.’

Which I would put together with Caliban’s lines: ‘in dreaming, / The clouds methought would open, and show riches / Ready to drop upon me; that, when I waked, / I cried to dream again.’ With it I’m simply trying to provide the audience an alternative perspective; a glimpse of the beauty of the culture of water before the installation of the desalination plant in 1965.

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.