Bruno / culturala

Your film ölmondnacht is cut from scenes from various films by Soviet necrorealist (so, the combined themes of death – necro – and of real life – realism) Yevgeni Yufit. How did you first encounter Yufit’s films? And why did you decide to work with his films specifically?

Anna

I discovered Yufit’s films long ago in a now gone and mythical place called Surrealmoviez, which was a great film sharing forum for rare, experimental and weird films & videos. This forum was the most important place for my artistic development – and a great way to explore film history.

I enjoy noise music, and so the term necrorealism instantly drew me in. I already loved Tarkovsky’s slow films, especially his depiction of nature, so finding Yufit’s mixture of nihilistic absurdities and beautifully captured landscapes was perfect.

The inspiration and urgent need to make ölmondnacht came shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. I was desperately sad. At the time, although unrelated to the war, I was also experiencing some online harassment. Somehow the atrociousness of the news and the absurdly angry messages I was receiving at that time reminded me of the grotesque happenings in Yufit’s films and I felt the urge to process his films through my own pain.

culturala

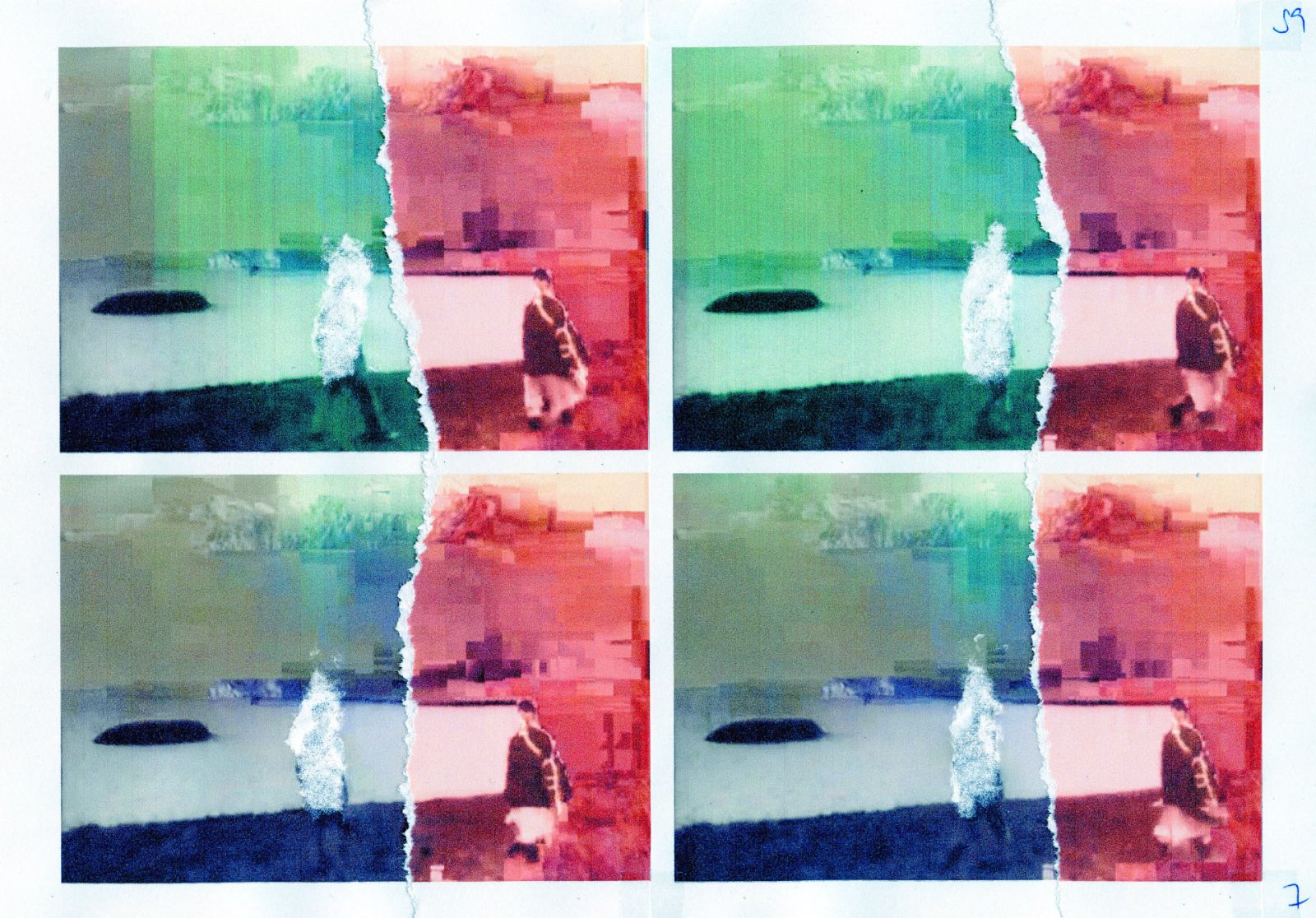

You speak of not only re-cutting his films, but also printing stills with a depleted inkjet printer and working with the physical distortions that come out as a result. It’s a very interesting technique. I know that you have also spoken of working with physical materials like paper, acrylics, charcoal, and translating these into digital animations for other works. How did this use of physical methods influence the piece itself?

Anna

Yes, I not only re-cut them, I also datamoshed them [digitally manipulating the images] before printing and further manipulating the paper. The initial idea was to just process the new cut with datamoshing, but as I’m always drawn to work in the back-and-forth between physical and digital, I printed some frames to see if it would add anything interesting. The emptying ink cartridges produced images that were even more unstable. The colours were off but vibrant, and I loved the results so much that I added this step of physical glitches and further hand manipulation by tearing off parts, collaging, and applying water to the prints.

I have always enjoyed working with physical materials because they force a certain kind of limitation, struggle and accidental discovery. Nowadays, I’m also able to find this kind of physicality in digital tools and materials, and explore them more often. But tearing paper with your hands or smudging charcoal with your fingertips fosters a special embodied and intuitive process for me. And all materials have their own characteristics that wait to be discovered, used and abused, and charged with meaning.

culturala

I’m very interested in the idea of a “discrete poetic world” as Vivian Sobchack writes about in Nostalgia for a Digital Object: Regrets on the Quickening of QuickTime. Sobschack writes that this discrete poetic world can be created in the Quicktime movie, as opposed to the “extensive, horizontal scope and horizontal vision of cinema.” How does this relate to your re-adaptation of Yufit’s films? Do you think your audience will relate to your films in ways different to those of Yufit’s?

Anna

I would relate Vivian Sobchack’s ideas about Quicktime movies more to gifs. At least this is where I consciously try to make encapsulated miniatures that spin out of tune with the normal time of the world.

But being a short film, as opposed to the full-length films of Yufit that I used, this idea can relate to ölmondnacht too, especially as it is also structured as a loop. As an experimental film, the narrative is quite vague and more intuitive, hopefully functioning more on a perceptual level than an intellectual one.

In terms of ölmundnacht’s potential audience, I find it difficult to say in what ways the films may be perceived differently, as not many people are familiar with Yufit’s films. Surely it’s easier to watch a ~6 minute film than a full-length one, but if someone likes ölmondnacht chances are that they might have the curiosity and open-mindedness to watch a film by Yufit too.

culturala

Could you perhaps clarify what is particular about pre-Soviet, Soviet & post-Soviet films? Do you notice differences between these three stages, and how do these inform the creation of your work?

Anna

The first decades of cinema are inherently interesting just because of all the experimenting and inventiveness. Soviet cinema is primarily known for montage and people like Vertov, Eisenstein and Kuleshov. But they didn’t appear out of nowhere and were in fact drawing on filmmakers and editors like Yevgeni Bauer or Elizaveta Svilova who were already working in imperial russia. Svilova, for example, would later work with Dziga Vertov.

I’m particularly familiar with films of the years 1919-1953, as I use those for my diploma project. There is certainly a noticeable shift into propagandistic storytelling, while the films before were often concerned with the psychology and morals of their characters. Late Stalinist films of 1950-1953 are especially oppressive in their propagandistic content. While beautifully filmed in 50s colours, the stories they tell and the kind of human they evoke felt suffocating to me in an intensity I didn’t expect.

Post-Soviet cinema is the one I am least familiar with, though from the films that I have seen, there is a general tendency of nihilism, violence and absurdity that is very similar to Yufit’s cinema.

Soviet cinema only informs a certain portion of my work that is directly concerned with the exploration of film and personal history. Compared to my other work, it is a more theoretical examination and questioning, where my artistic work is a means of research into this field and an opportunity to transform my curiosity and thoughts into something palpable.

culturala

You also mention Yufit’s representation of bodies “in a state of endless dying”, in relation to the genre of necrorealism which deals with themes of death and representation of real life. How does this contrasting idea of a living death translate into your film? Or, perhaps, how do you see this in contrast to the idea of a “live-action” film?

Anna

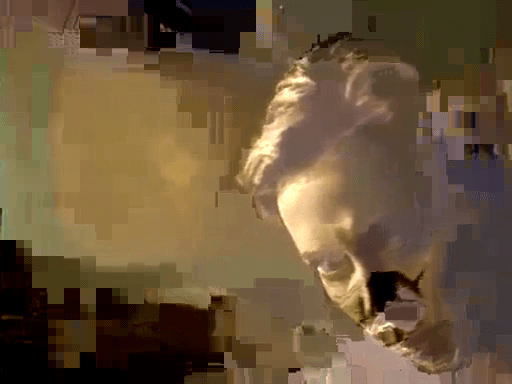

There is this seeming dichotomy of live-action and animation, but at least in analog live-action film and in frame by frame animation, they both function in the same way; as discrete frames at a certain speed acquiring a flow and perceptible realistic motion. I think this is what I find interesting in combining live-action footage of a film with the animation of materials like paper. Both the image and what is represented in the image as well as the materials that make the image perceptible, like paper and ink, are animated by the same principle, so everything you see in that animation has the same status and exists in the same dimension. A visible figure is as much a moving character as a paper tear. I think this is what makes films supernatural.

Already in one of the earliest pre-Soviet texts on cinema in 1896, Maxim Gorky describes his first viewing of films by the Lumière’s as a visit to the “Kingdom of Shadows.” Gorky desccribes this like this: “It is not life but its shadow,” and “Their smiles are lifeless, even though their movements are full of living energy and are so swift as to be almost imperceptible. … It is terrifying to see, but it is the movement of shadows, only of shadows…”

And so, cinema is often perceived to possess a haunting quality. With older films, this feels even more so since they are now populated with so many deceased people whose images and voices can be activated instantly. I find this haunting quality of film very interesting, as it can also be seen as a real-world manifestation of something like “time travel” and “alternative realities.” You can “meet” dead people or see places that were dramatically transformed and look nothing like when they were filmed.

ГАН ЕСКАПІЗМ by Anna Malina.

Music by Ryan Campos.

culturala

Can you expand a bit more on the relationship between landscape and film in your works? You say that in analog fictional films a landscape carries “a trace of reality in it.” What do you mean by this, and what do you aim to do with that reality?

Anna

It’s just this simple idea that if you shoot a fictional film in a real place (as opposed to a stage or studio set), you have a document of that real place, even if the film is fictional. So there are films that become more interesting or charged with new meanings beyond their initial ideas over the years, because they contain something that has changed or is not there anymore; films that gain a documentary quality, even if that was not intended when it was made.

This is the initial thought that underlies my projects where I use footage from Soviet cinema: What can I see in or learn from these traces of reality? I was a child when my parents and I migrated from Soviet Ukraine to Germany; shortly after that the Soviet Union ceased to exist and I have never been back to where I was born since then. So this idea is like a nice theoretical excuse for an engagement with films and film history and for taking cinema seriously as a producer of cultural and historical artifacts.

The GAN footage i used in ГАН ЕСКАПІЗМ [GAN ESCAPISM], as well as in Shadow Projection, is made from data sets I made from around 90 pre-Soviet fictional films ranging from 1908-1918.

Coincidentally, in both cases the sequences are made from a model trained on film stills where only women are present. (I made a variety of data sets with topics like Landscapes with people and Landscapes without people, Interiors, Intertitles, & more)

In the case of ГАН ЕСКАПІЗМ i constructed the sequence specifically for the music of Ryan Campos. I used this same track, but edited, for the actual still unreleased GAN short film.

But to also release this track in its original version I made this sequence, trying to express its mood and affect it has on me.

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.