Maria / culturala

Can you tell me a little bit about the scenes we see in the film? Who was involved in making it, who are the people we see? They’re your family, right?

Diana

I started filming in December 2019. I was home during the holidays and we have the tradition that on December 23 you make tamales for Christmas. The tradition is to make them with all generations of women in the kitchen. My great-grandmother, grandmother, mother, sister, and I were in the kitchen early morning that year and we didn’t finish making the tamales until late into night. To be honest, when I was younger I was always resisting this tradition. The labor and time that it takes to make tamales is exhausting. The kitchen gets so hot and you’re getting masa all over the place. I have so many memories of the smell of pork, chicken, cheese, and masa lingering in the kitchen for weeks. And I can’t pinpoint the uneasy feeling of making tamales every year. It’s not an exact space. It’s like a multi-layer, multi-generational, overreaching, overlooking, overpassing, and overconsumption of time that gives me a feeling of uneasiness.

So that scene of the tamales and hands is from that year. I found another way I could participate in the kitchen by filming. Capturing images. I was so focused on everyone’s hands. How everyone had such a different style of embarrar los tamales. Spreading the masa on tamal husk. I found a fascination with how my little sister did the spreading. She was eight years old at the time and already learning how to do it. But not only learning, wanting and sitting there for hours doing the preparation because she enjoyed it. This film is dedicated to her. Demi Sophia.

All of the other scenes are filmed from 2019-2022 during my short visits back home. I have an on-and-off relationship with the Texas landscape. Everyone in it is my family. The voices. Transitions. Textures. Colors. Sounds. Patterns. It’s all them.

It’s interesting to think that this moment was filmed because as a family we will never have a year like 2019 in the kitchen. There will never be a day of making tamales like that year.

culturala

The song in the beginning is incredible. What is it we’re hearing there and what do the lyrics say?

Diana

The song, in the beginning, is Las Mañanitas. It’s a birthday song. The recording of that song was made on my step-father’s birthday two years ago. We got him his favorite cake, tres leches, and sang to him outside on a patio. I don’t know what called me to record my family singing happy birthday to him that day, but I did. I grew up with this song in my head so often.

When I started editing Donde Cocinamos I knew I wanted to include the recording. I just wasn’t sure where exactly and when I placed it at the beginning of the film it provoked an awakening for me. I began thinking about the song in different terms. Different circumstances. The first lyrics of the song are Estas son las mañanitas, que cantaba el rey David Hoy por ser dia de tu santo te las cantamos aquí despierta, mi bien, despierta

This can be translated to these are the mornings who sang to king David, today for being the day of your saint we sing them to you here, wake my good one wake up, and it goes on to say look it has awoken the birds are singing the moon has gone inside the morning is beautiful and we can to celebrate you.

It’s a quite beautiful song. With so much joy to encounter the rest of your day. A special day can be the day you were born. And usually, birthdays were referred to as the day of your saint. El Día de tu Santo. Every day in many catholic calendars, there is a saint associated with the date. Many people are named after the saint of the day they were born in. It is interesting to look up someone’s saint on the day they were born. To see the connections, the gifts, or protection they were given because of this. I wasn’t named after the saint of my birthday but I do think about them.

The song, in the beginning, is sort of a birthday song to the film. A song for the film to wake up to. It creates this entering of the film, a giving, an appreciation for the images, and sounds for their existence.

culturala

There’s a lot of nostalgia and a “taste of home” that I feel even though it doesn’t depict anything like my own home. Where do you think this homeliness comes from? And what did you do to evoke that feeling?

Diana

I’m unsure if I did something specific to evoke that feeling. Or maybe I did everything to evoke that feeling. I believe a lot of the color creates that nostalgia for some viewers. The black and white. The faded film edit. Color has a great way of doing that.

For me, this very current thought & feeling that home isn’t a nostalgic space anymore. I had a friend watch this film and then tell me “It’s like I’m looking back at the way the world was before the apocalypse.” The film in a way provoked the realities we lived in before the pandemic. If anything the film was illustrating those realities and yet contemplates, and analyzes how some current times are still trying to fit into something that used to exist. We can’t return to those spaces anymore. This current reality does not fit the reality where all five generations of women are cooking tamales in the kitchen.

Perhaps that is where the nostalgia arises for everyone. The knowing or acknowledgment of a time that existed for all of us and the shared experience of loss & grief to those times.

The sense of home is now being redefined for me. It’s a reorientation in which home is not a location, or place but a carving of specific details which fixate themselves in sensory overlaps. Is this the homeliness feeling in the film?

culturala

Your first line is “hay una historia que…” and you work a lot with different ways of storytelling. What did you discover when delving into the stories that built up Donde Cocinamos? How do you use storytelling in your work in poetry, performance, film, and painting?

Diana

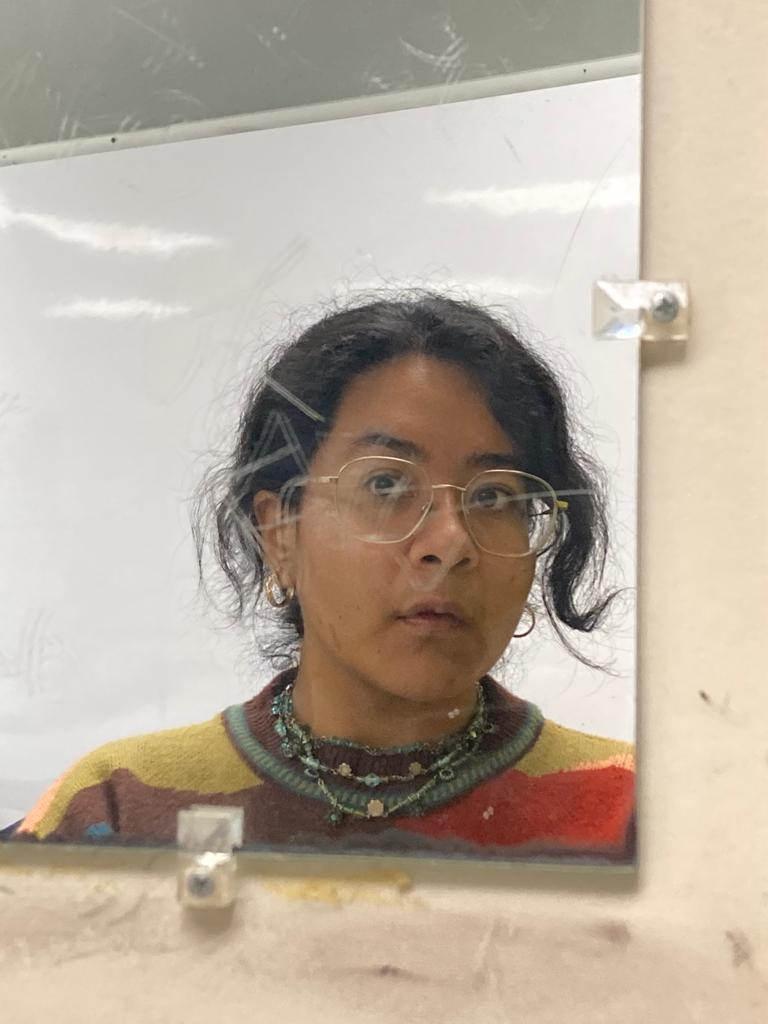

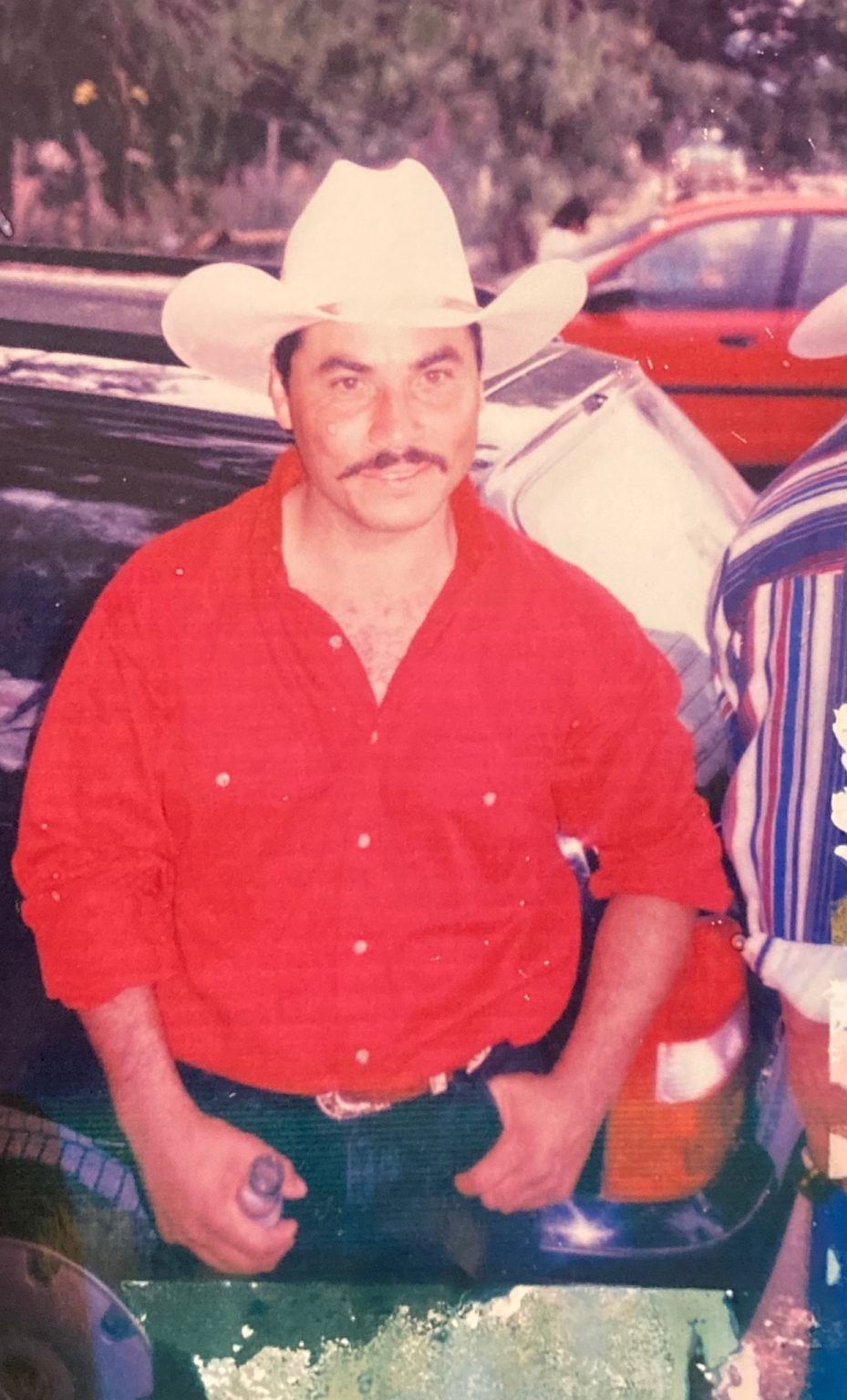

The line “hay una historia que,” gives you a fragment of what is happening. Or what is about to happen. It is one of the only vocal senses of narrative happening in the film. That line and the specific scene are a reference to my father. His story of how he came to the United States. He train hopped at a young age from Mexico across the US border. I believe he did this a couple of times. Not just once. And it’s an unclear story for me still with not many details. Even recalling it now it seems as if I have gotten an image of him laying down on the train looking up at the sky with its indifference to where the border lies.

Narratives. Storytelling is always building itself in my poetry, performance, film, and poetry. And never in the traditional or linear ways some narratives exist in.

culturala

In the second half of the film, I get this feeling of dread. Of things going missing, things being hidden. I start thinking about hurt and loss and the inability to reach that homely feeling of safety, as if by covering the lens with that thin veil, you’ve veiled this blissful reality from me. It also makes me think of your recent project seen / unseen. What have you discovered happens when you play with that dichotomy?

Diana

I often work with the unseen / seen. Layers. Textures. Loss. As the years go you become more aware of these veiling and unveiling cycles.

The usage of fabric in a sense is the usage of raw material. The ability to create, sew and weave fabrics, textiles, patterns, and textures. The covering of the lens in a way is both veiling and unveiling the fabrications of what it is to make a film. It is a process being revealed. But yet hiding the images or voices that film inhabits.

At the time of filming those moments, I was learning how to sew a dress. How to make a piece of clothing from scratch. I had to learn that. I had to learn how my hands moved with the needle. The experience gave me what I needed to learn more about the film itself. The tying. The breaking. The tightness of fabric against thread and needle.

And I come back to the words raw material because essentially this is what a filmmaker has to begin with. Raw images. Raw movement. Raw audio. And you develop a pattern to see how long a sleeve should be, or how tight the waistline must fit. You learn how to make a piece of clothing.

This idea of working with a dichotomy is interesting. As I feel the constant experiences of being able to work with opposites. Facing energies. Positives and Negatives. Mirrors. Two different slopes in the opposing y and x axis.

I find a lot of wisdom to bring two energies into a space, into a piece of work.

The need to bring two energies is the acknowledgment that two energies shouldn’t be the same. And find the value on how similar, but different. Positive and negative energies interact as connecting factors & alignments to what one energy can create in which the other can’t. And vice versa.

Isn’t there something exciting about that? Tension? Vision and expanding perspectives happening because of the opposing energies. But also the ability of an interconnectedness regardless of how opposite certain energies are.

culturala

Continuing to speak about what happens later in the film, we see that feeling of dread deepening. There’s a white, winter tree landscape, and then an insect covered in flies. What does all of that symbolise for you?

Diana

Everything returns back or becomes an extension of itself. The tree landscape and the cicada are covered in ants. Is a returning back to some of my early work called La Cigarra en los Retoños which is a multimedia collection of many writings, photographs, installations, paintings, and film. These scenes are a reference to that body of work.

I thought it was important to return to these images because it was a moment of memory. A moment to witness a single trail or multiplicities in which my work has come from and gone. The Texas landscapes I return to are built with those details of the tree and cicada.

Some photographs from La Cigarra en los Retoños.

culturala

Continuing to speak about what happens later in the film, we see that feeling of dread deepening. There’s a white, winter tree landscape, and then an insect covered in flies. What does all of that symbolise for you?

Diana

Everything returns back or becomes an extension of itself. The tree landscape and the cicada are covered in ants. Is a returning back to some of my early work called La Cigarra en los Retoños which is a multimedia collection of many writings, photographs, installations, paintings, and film. These scenes are a reference to that body of work.

I thought it was important to return to these images because it was a moment of memory. A moment to witness a single trail or multiplicities in which my work has come from and gone. The Texas landscapes I return to are built with those details of the tree and cicada.

culturala

What was your most interesting discovery while you were making Donde Cocinamos? What did you learn?

Diana

The most interesting discovery I had about the film was recent. I was sitting with my grandparents showing them the film when I realized something about the dance scenes. It was transportation to many childhood memories of being asleep during late parties. But also the footage that is recorded for those specific events is something I had forgotten about. And how recalling that type of footage made me realize that these were my first experiences with the film. How I was now recreating this form in my own ways.

Like during a baptism, quinceñera, and other celebrations usually there would be someone recording the whole event. The recording sometimes becomes mostly footage of people dancing. It illustrates how dancing becomes this phenomenon in spaces of celebration.

There is one scene where I am layering a couple of dancing, fast and with so much rhythm to each other’s bodies. I filmed this one day when we were out getting fruta from a fruteria. They had a tv playing this footage of people dancing at a rodeo of some sort gathering. Everyone who was recorded was so present, alive to the space and the bodies that surrounded them. It becomes a sort of performance but not one for the camera. It’s a capturing. It’s a demonstrated sensation of what it means to come together and be in rhythm with each other’s bodies.

culturala

In the final part, the film jumps back and forth, as memories that we’re forgetting and remembering. What role do memories play in your work?

Diana

Memory is this jumping back and forth. It is the essential foundation one must learn to allow to collapse and reform. It transforms time.

And it happens in many different ways throughout this film. Just as I mentioned the cicada and the tree as a memory. Memory as my great-grandmother telling stories about her childhood in Mexico while making tamales. Memory as the sounds of a birthday song ringing in my ears. Memory of my father crossing the border on a train. Memory the smell of pork and masa. Memory as the portraits of my grandmother and grandfather in the first scenes & the repetition of those scenes. Memory of the music that played loud late at night while I slept on my mothers lap. Memory of my sisters hands. Memory of beans. Memory of light hitting the pond of my favorite park.

Memory becoming a filter. Memory becoming space. Memory becoming color. Memory becoming sky. Memory becoming a filter. Memory forgetting and then remembering itself.

We use cookies to make sure you get the best out of our presence, and by using our website, you agree to our use of cookies. For more information, read our Policies or reach out to us by email.